Last month, the BBC published an article “Is this Switzerland’s Schindler?” about a Swiss man named Carl Lutz who used his position as an envoy for neutral Switzerland stationed in Budapest to issue letters to thousands of Hungarian Jews during the Second World War. These special letters extended Lutz’s diplomatic protection to those targeted for deportation. Lutz saved an astounding 62,000 Jews from being sent to the concentration camps.

Crowds expecting to be deported gather outside Carl Lutz’ office in Budapest to get protective letters in late 1944 (photo credit). Notably, Carl Lutz not only issued letters to individuals and families, but also 76 buildings that housed these groups. The Glass House survives today as a result of Lutz’s intervention.

It’s a very remarkable story. Not only does it demonstrate the extent to which people in positions of power could sacrifice their own safety for the survival of total strangers, but it also exemplifies how Swiss citizens could mobilise their government’s neutral status in WWII to help victims of persecution.

Shortly after this article was published, a friend contacted me and, knowing that I studied Switzerland during the Second World War, asked me about Switzerland’s wartime humanitarian efforts: But Chelsea, didn’t the Swiss create the Red Cross? And weren’t they neutral during the war? If so, did they help protect Jews during the war through the Red Cross? And what about refugees fleeing the Nazis? Honestly, why didn’t every single person just pack their bags and move to Switzerland during the war?

These are all excellent questions. Switzerland’s neutrality certainly means that it had a unique position in wartime Europe. Combined with its history of humanitarianism (yes, it did create the International Committee of the Red Cross), and its convenient geography in central Europe (bordering Austria, Germany, France, Italy and Liechtenstein), Switzerland appears to be perfect hiding spot from the Nazis, and a country that could manoeuvre through tense wartime diplomacy to help victims of war. Well spotted, my friend.

Added to all these facts was (and remains) Switzerland’s strong legacy of banking (supported by valuable privacy laws). Foreign investors still flock to Swiss banks because of its centuries of neutrality (and thus financial stability during war), including foreign governments. In fact, some scholars argue Switzerland’s ability to financially shelter governments’ investments was the single reason that it was not invaded during the war – Swiss banks were just too valuable to both the Allied governments and Nazi Germany’s financial health to even consider crossing one platoon into its little alpine territory.

So really, we have three non-negotiable factors that influenced (and continue to influence) Switzerland’s political actions: neutrality, humanitarianism and banking. Remarkably, Switzerland protected its geographic borders from invasion in both World Wars due to its ability to maintain amicable relationships with belligerent nations. It provided them with a neutral trading centre (ie. banks and foreign currency), as well as becoming an intermediary for international organizations, such as the League of Nations. This tradition still stands today.

Today, if you’re lucky enough to be able to afford a trip to Geneva, you can walk past the United Nations (above), the headquarters of the World Health Organisation, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the International Labour Office and the World Trade Organisation – all a stone’s throw from the same street! (And you’ll have to walk because you won’t be able to afford anything else).

Although Switzerland’s neutrality, humanitarianism and banking can be seen as massive opportunities and methods to help others, they were often used as excuses by Swiss authorities to limit, evade, or reject multiple initiatives that would have saved countless lives during the Second World War.

However, in keeping with the optimism and sacrifice that Carl Lutz has shown the world, I will write about one extraordinary example where Swiss citizens overcame these limitations to provide refuge and relief to one of the most vulnerable groups suffering under Nazi rule – children.

Why would the Swiss government reject humanitarian initiatives?

Ultimately, Switzerland feared being overrun by refugees. As Switzerland depended on warring countries for its imports (about 55%) and exports (about 60%), there was simply not enough resources to ensure its national survival if thousands of foreigners (even refugees) came to stay. Over half of the coal in Switzerland, for example, originated from Nazi Germany’s monthly shipments. Thus, Switzerland had to balance national survival with shrewd financial decisions. (For more on Swiss wartime economy, see Herbert Reginbogin’s [2009] Faces of Neutrality, and Georges-André Chevallaz’s [2001] The Challenge of Neutrality, Diplomacy and the Defense of Switzerland).

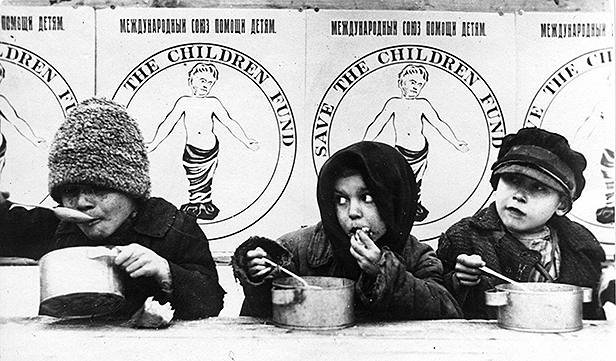

Similar to today, Europe was overwhelmed with refugees still displaced by the First World War, the Turkish-Armenian War, the Russian Civil War, and the impact of famines gripping eastern Europe. Similar to today, refugees were not simply a passing trend.

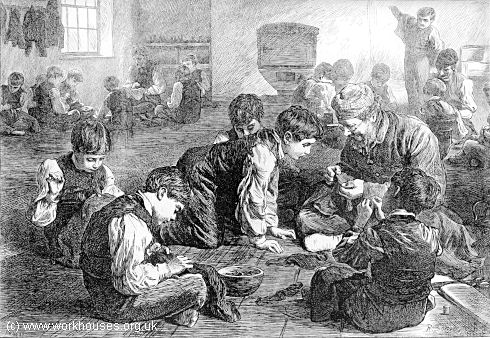

Multiple charities helped refugees in the wake of the First World War. By 1921, when the Russian Civil War had produced countless refugees and starving children, the Save the Children Fund had found it’s stride. It campaigned on the big screen by showing films of the conditions children faced to British audiences. For a brief history, see here.

By the end of 1933, the first year of power for the Nazis, some 37,000 Jews had voluntarily emigrated from Germany as a direct result of increasing violence and persecution (RJ Evans, Third Reich in Power). With Germany’s introduction of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 – stripping all Jews in Germany or Austria of their citizenship and thus making them stateless refugees in their own country – the world began to realise it had a growing refugee crisis on its hands, especially if Hitler’s militarisation of Germany continued to go unchallenged. Despite this, countries like France and Britain were apathetic to the plight of these refugees, instead being more concerned with unemployment or other domestic issues (Claudena Skran, Refugees in Inter-war Europe). Sounds like the recent situation in Calais, no?

But refugees had protected rights. In 1933, refugees gained internationally recognised rights (to passports, for example) for the first time, granted by the League of Nations (which, notably, Germany withdrew from in 1933). But this did not equate to decent treatment or immediate asylum for refugees worldwide. In fact, it still doesn’t. (See how refugees today are treated in Libyan detention centres).

In 1938, President Roosevelt’s administration organized the Evian Conference in France to help coordinate efforts to facilitate the emigration of refugees from Germany and Austria. But the conference was unsuccessful, because most participating nations seemed more concerned with turning the refugees away from their own borders or, in the case of Britain, by simply refusing to contribute to it (Skran, Refugees in Inter-war Europe, 280).

Lord Winterton, the English representative at the Evian Conference, gives a speech to attendees (photo credit). TIME reported on 18 July 1938, “Britain, France, Belgium pleaded that they had already absorbed their capacity, Australia turned in a flat ‘No’ to Jews, and the U. S. announced that she would combine her former annual Austrian immigration quota with her German to admit 27,370 persons (who can support themselves) from Greater Germany next year.”

Switzerland’s delegate, Heinrich Rothmund (the Chief of Police and responsible for Swiss borders and immigration), argued that larger countries, such as the US, should absorb large numbers of refugees so that European nations could operate as merely transit countries. Seems logical, eh? However, this line of policy was not accepted. By the time the Second World War broke out, very few legal stipulations existed which governed the admission and rejection of refugees, and, instead, refugees had to rely upon the decisions made by individual countries. The League of Nations, and the international community, had ultimately failed to protect refugees in time for war.

By late 1938, Rothmund’s idea to treat Switzerland as a transit country had failed. Escalating Nazi persecution (and the annexation of Austria) caused more fleeing Jews to congregate at Swiss borders. At this point, Rothmund decided that all refugees without visas, especially Jews, would be rejected from Swiss borders. Switzerland then implemented a new, discriminatory method of stamping all Jewish passports and visas with a large J (J for “Jude” meaning “Jew”). This “J-stamp” method to clearly distinguish Jews from other refugees was recommended to Nazi officials by a Swiss legation in 1938. Unfortunately, the Nazis adopted this into their own immigration and deportation protocols. (For a collector’s example, see here).

Amidst public outcry, Switzerland closed its borders in August 1942, justified by Swiss authorities due to an alleged lack of resources. The border closures remain one of the darkest chapters of Swiss history as Swiss actions directly impacted refugees, forcing many refugees to face persecution and death (This was a major finding of a large 25-volume Swiss government-commissioned study in the 1990s, see here). And, in November 1942, when Germany invaded southern unoccupied France, fresh waves of refugees fled to Switzerland’s strictly controlled borders; most were turned away, resulting, for some, in eventual deportation to mass extermination camps. By late 1942, Swiss refugee policies slowly changed, but it was not until July 1944 that the border opened again fully to Jewish refugees.

Switzerland’s Wartime Dilemma: How to Help Refugees when Limited by (an anti-Semitic and anti-refugee) government?

Similar to so many countries today, private citizens vehemently disagreed with their government’s restrictive border controls to limit the intake of refugees. This friction provoked Swiss civilians to turn to non-governmental organizations to help victims of war they deemed worthy of their donations, relief and aid.

One key example is the “Swiss Coalition for Relief to Child War Victims” (Schweizerische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für kriegsgeschädigte Kinder, or Le cartel Suisse de secours aux enfants victimes de la guerre). A mouthful, I know, but let’s call this group the “Swiss Coalition.”

The Swiss Coalition was an alliance of seventeen Swiss charities that sought to evacuate children from war-torn Europe to Switzerland. Although it had operated successfully during the Spanish Civil War (evacuating over 34,000 child refugees of the Spanish Civil War to multiple host nations), this “new” Swiss Coalition was bigger, prepared and practiced. Importantly, remaining funds from its Spanish operations were liquidated and added to the new coalition’s purse.

In 1940, the Swiss Coalition began its remarkable work. Raising over 700,000 Swiss francs in one year alone, the Swiss Coalition appealed to the humanitarian spirit of the Swiss people. One initiative encouraged thousands of Swiss families to voluntarily host children from southern France (then unoccupied by Nazi forces) for three months in their own homes. This ingenious method bypassed Switzerland’s strict immigration controls, as the children would not be a perpetual national burden, as well as appearing more attractive to Swiss hosts, as the children would not be a permanent family commitment.

When children arrived, they gave their information to Red Cross workers who then compared it to the transport manifest and reported it to immigration authorities. After medical screening and delousing at Swiss train stations, they received their first warm meal in Switzerland. (Photographer Hans Staub. Basel train station, circa 1942. CH-BAR J2.15 1969/7 BD116, Belgische Kinder kommen (nach Basel), circa 1942).

The measure was extremely popular among the public, and by November 1940, when the first evacuations from unoccupied France began, the number of families volunteering to host children actually outnumbered the children selected for evacuation. Thousands of families offered spots for French children; over 2,000 were offered in Geneva alone. By December 1941, the Swiss Coalition hosted more than 7,000 children in Switzerland, the majority of them French (Swiss Federal Archives, CH-BAR E2001D 1968/74 BD 16 D.009 14 and Antonie Schmidlin, Eine andere Schweiz, 137).

Notice the fatigue from this little Belgian boy. The captain reads “Arrival of Belgian child convoys in a Swiss train station. The children have travelled all night, have slept little and are now hungry and tired.” (Photographer Kling-Jenny. CH-BAR J2.15 1969/7 BD116, Belgische Kinder kommen (nach Basel), circa 1942).

The success continued and operations enlarged. Surprisingly, Nazi authorities agreed to temporary evacuations from their occupied zone, as it was hardly an inconvenience for them; the Swiss operated and funded the evacuations and – crucially – Switzerland was neutral. In February 1941, child evacuations from German-occupied northern France began, and the Swiss Coalition was the first foreign agency allowed into blocked areas, such as Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne.

Medical assessment was the chief criterion for selection. Due to the typhoid epidemics in late 1940 and summer 1943 in northern France and rampant diphtheria during the winter of 1942-43, it was necessary to protect the children, and the Swiss hosts, from such diseases. (CH-BAR J2.15 1969/7 BD 114, Kindertransporte aus Frankreich, March 1942).

In 1942, Belgian children suffering under Nazi rule were now evacuated. Generous donations from Swiss citizens continued to pour in and the Swiss Red Cross joined the operations. This was an important moment because it meant that the national Red Cross infrastructure (and doctors) could be utilised. This was certainly a formidable humanitarian operation.

Strict immigration controls still existed though. By mid 1942, Kinderzüge, or special Children’s Trains, were only allowed to travel one day per week. It had to be the same day every week. Maximum 830 per train. Only 1 adult per 30 children. According to Heinrich Rothmund’s office, there was to be absolutely no deviation from the following criteria:

- Only children with appropriate identity papers (passports) that allowed them to return to France or Belgium could be selected. This was difficult for stateless groups, such as Jewish families who had left fled Germany or Austria for France. Importantly, this meant that no German-Jews could be evacuated. This also ensured that no child became a responsibility of the Swiss government.

- Poor health was the sole criterion for selecting children (secondary to having the correct identity papers, of course).

- Children had to be selected by Swiss Coalition doctors and medically screened upon arrival in Switzerland.

- Children had to be 4 years to 14 years old.

- Swiss Federal Police have the full authority to reject children upon entry on any grounds for any reason.

Once the children arrived in Switzerland, there was a host of additional criteria they had to follow while residents in Switzerland. While you could argue that these pedantic rules prevented children from becoming lost or abused by their hosts, it also meant that no one could abuse this temporary system of asylum. No Swiss host could extend a child’s stay, for example.

Rothmund specified that Medical Corps of the Swiss Frontier Guards (above) had to deem the children physically poor in order for admission into Switzerland. If entry was refused, then children were not to cross the Swiss border and were immediately returned to their home country. I’ve found no direct evidence to reveal that children were rejected. (CH-BAR J2.15 1969/7 BD116, Belgische Kinder kommen (nach Basel), circa 1942).

Despite the impressive enterprise, the Germans terminated the evacuations from Belgium in May 1942 and from France in October 1942. Their justification was based upon the belief that children in Switzerland would become politically incited with anti-German sentiments. (Yep, really).

The Nazis’ termination of these three-month evacuations coincided with Swiss border closures in late 1942. (But it is important to point out that some children gained entry into Switzerland, including those admitted due to tuberculosis and others sent through another initiative led by Pro Juventute). It was not until July 1944 when the Swiss Coalition resumed the three-month evacuations.

In total, over 60,000 French and Belgian children benefitted from these temporary child evacuations (including some from Yugoslavia) during the Second World War. In the post-war period, this was expanded to other war-stricken nations and an additional 100,000 children were welcomed to Switzerland from 1945 to 1949.

So what?

While I discuss Switzerland at length here, the obligations among so-called “neutral” nations to help refugees is not just about Switzerland. If we put any nation under a microscope, we will discover many unwelcome truths about its immigration policies. Assigning responsibility (and culpability) for who did or did not protect refugees, including Jews, is a tricky exercise, especially when discussed on such a large, international scale.

Perhaps Swiss historians say it best. When ascribing responsibility for Switzerland’s lack of action to protect vulnerable groups, notable Swiss historian Edgar Bonjour argued that the entire generation of Swiss made it possible for the democratic government to create such refugee policies. Historian Stephen Mächler (Hilfe und Ohnmacht, 440) pushes this further to criticize “the entire globe,” as everyone opposed welcoming refugees, especially Jews, making it nearly impossible for Switzerland to do anything but to create similar refugee policies. However, as Georg Kreis argues (Switzerland and the Second World War, 113), if all are responsible, then ultimately no one is responsible

Let’s return to our “Swiss Schindler”. As a diplomat working from a Swiss consulate in Budapest, Carl Lutz was protected by international law and granted immunity to local conflict, as any diplomat should be treated. But, importantly, only neutral governments during the Second World War could act as protective powers. As Lutz was the citizen of a neutral government, this meant that his Swiss embassy in Budapest acted as an intermediary and/or protective power for other warring nations without diplomatic representation in Hungary. (This system still operates today; a Canadian pastor was recently released in North Korea via the Swedish embassy because Canada designated Sweden to be its protective power). Therefore, Carl Lutz’s citizenship to neutral Switzerland played an incredibly critical role in the lives of 62,000 Jews.

Remarkable initiatives like the Swiss Coalition, and the actions of Swiss citizens like Carl Lutz, Paul Grüninger, Hans Schaffert, Roslï Näf, and so many others, deserve great attention. They not only sacrificed their own personal comfort, safety and even careers, but they discovered cunning ways to capitalise on their Swiss neutrality for the protection of thousands of people. In this sense, their humanitarianism (and courage) seems amplified. Neutrality was not a limitation or excuse to not intervene, but actually an influential weapon that could be used, if in the right hands.