This past week, I’ve been doing some freelance research for a British human rights charity. This experience has dramatically opened my eyes to the absolute chaos that is the British “immigration” system.

Of course, we’ve all heard about British government’s fumbling inability to handle current refugees and even integrate migrants. Windrush Scandal, anyone? Or Theresa May’s explicit wish since 2012 “to create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants”? Well, looks like it’s worked there, Prime Minister! How about the refusal to grant visas to 100+ Indian doctors, who had been especially recruited to help critical health shortages in the NHS? Or the ever-growing imprisonment of asylum seekers in British “detention facilities”? Or the fact that the Home Secretary herself had no idea that immigration quotas were used in her own department? So long, Amber Rudd.

But while I was scrutinising the absolute disorder and contradictory measures that the Home Office currently takes towards the world’s most vulnerable people – refugees, asylum seekers and victims of trafficking – I was delighted to discover that at least one portion of this Great Britain is taking deliberate, long-term steps towards helping these groups: Scotland.

Did you know that of all the UK, Scotland is the only nation that wants to give refugees the right to vote?

Hurrah! In May 2018, it was announced that plans are being proposed to the Scottish Parliament to give EU, non-EU and asylum seekers the right to vote. Let’s hope it passes!

But why is this a good thing? Giving migrants the right to vote is an absolute cornerstone of nations with a history of immigration and diversity. For example, Australia, the United States, and Canada have benefitted immensely from giving refugees, asylum seekers and other landed migrants the right to vote. Although, admittedly, this didn’t happen overnight. (For example, Japanese and aboriginals in Canada were not given the right to vote until 1949 and 1960, respectively). But in the 1970s, Canadian PM Pierre Trudeau flooded Canada with migrants and, by extension, new voters. Although it seems wonderfully inclusive, the true motive was to dilute existing Francophone and Anglophone tensions that were hitting a crisis point!

Trudeau’s strategy, however underhanded, achieved something remarkable. It meant that political parties had to include these new immigrants in their broader policy objectives. It meant that migrants were courted with initiatives that appealed directly to them. This forced politics to become dynamic, progressive and inclusive. Instead of pushing migrants to the fringes of society, this enforced that Canadians, whether new or native, were included in the most high-level decisions in Ottawa. In fact, in 2011 and 2015, the Canadian Conservative Party won a higher share of votes among immigrants than it did among native-born Canadians. Go figure.

Of course, if migrants in Scotland are given the right to vote, this allows the Scottish National Party (SNP), currently a significant minority party, an opportunity to expand its voter base. And, you know what? I don’t care. It doesn’t matter if you’re an SNP, Tory, Labour, Lib Dem or Green supporter. If migrants can vote, including EU and non-EU residents, then this only benefits greater Scottish society. Inclusivity and diversity will become ingrained in Scottish politics which, in turn, will impact Scottish voters, Scottish attitudes and broader long-term Scottish aims. This will irrevocably enrich Scottish society.

Also, increasing the rights of people who live here does not nullify or decrease the existing voter rights of born-and-bred Scots. Equal rights for others does not mean less rights for them. It’s not pie, right?

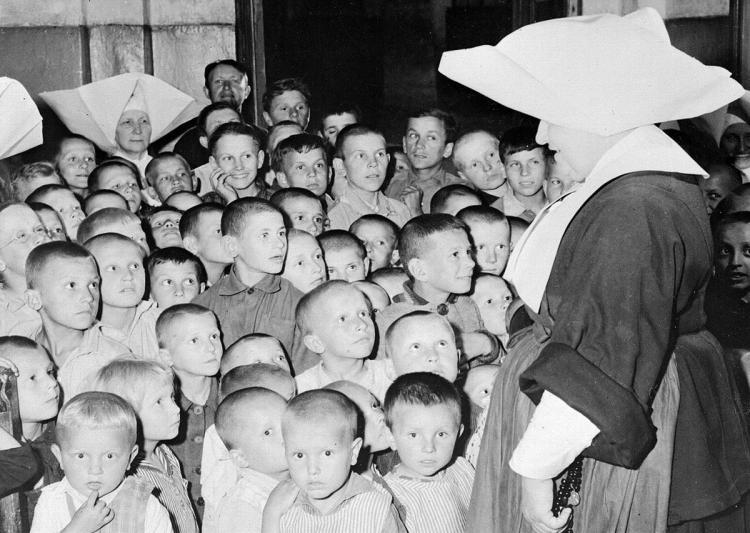

Green MSP Ross Greer said in May 2018, “What better way could we show refugees and asylum seekers that they truly are welcome and that Scotland is their home than by giving them the right to vote?” These Syrian refugees arrived in December 2017 to be settled on the Isle of Bute (Photo by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images).

Did you know that of all the UK, Scotland is the only nation to have an explicit strategy in place to integrate newly-arrived refugees?

To my absolute astonishment, England, Wales and Northern Ireland do not have any broader strategy to integrate its thousands of refugees and asylum seekers. Stupid, no? Fortunately, after mounting pressure, England announced last March that it will invest £50m to support an Integrated Communities Strategy that will initially target five local authorities in England to improve English language skills, increase economic opportunities (particularly for women) and ensure that every child receives an education. So, I guess late is better than never, eh?

But a lack of an “integration strategy” (however bureaucratic and boring that sounds) has massive impact on migrants. For example, asylum seekers in the UK face massive problems once they’re granted refugee status. After waiting six months for a decision (while surviving on just £37.75/week for yourself and dependents, with no right to work or access mainstream benefits, and living in shady Home Office accommodation outsourced to companies with a history of poor quality compliance, like G4S), you are given just 28 days to find work, a new home, apply for benefits, and “move on” towards integration.

This “move on” period is often the worst moment for refugees in the UK. Suicide rates spike, mental health problems increase, people are forced into destitution and exploitation simply due to a lack of support and, critically, not enough time.

In fact, the Home Office often does not send critical documentation to new refugees within this 28-day period. For example, a National Insurance Number (NINo) and Biometric Residence Permit become vital to a refugee’s survival in the UK because they often did not flee war and persecution in their homeland with their passports, right? So, one or both of these documents are required for gaining employment, opening a bank account, applying for a Home Office “integration loan” (£100+), accessing mainstream benefits and securing private or public accommodation. However, the Home Office often does not send these documents until well after an asylum seeker has been granted refugee status. Seems counterintuitive, no?

For example, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Refugees wrote in their report about Sami from Iraq. He was not sent his NINo until the day after he was evicted from his Home Office accommodation (at the end of the 28 day “move on” period). Because Sami could not claim benefits or obtain employment to secure accommodation without his NINo, he was forced into homelessness. Charity reports are riddled with stories like these, where it’s obvious that the UK’s current system is failing those it most means to help. Instead, homelessness, destitution and exploitation become synonymous with the refugee experience.

After the “move on” period, refugees now have the long-term task to integrate. Learning English is, obviously, the biggest task. Without being able to communicate, migrants cannot access NHS services, higher education or training, the job market, or even just simple things like community events! So, English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes are vital, right? But in England, government funding for ESOL classes was drastically reduced by 55% between 2008 to 2015. Fortunately, Scotland and Wales and Northern Ireland all currently have ESOL strategies in place. Nearly 5% of all Scots (over age of 3 years old) actually speak another language other than English in the home. Although Brits are generally notorious for not speaking other languages, at least the Scottish government is wise enough to support these refugees learning English. This, sadly, is something they’re failing to do south of Hadrian’s Wall.

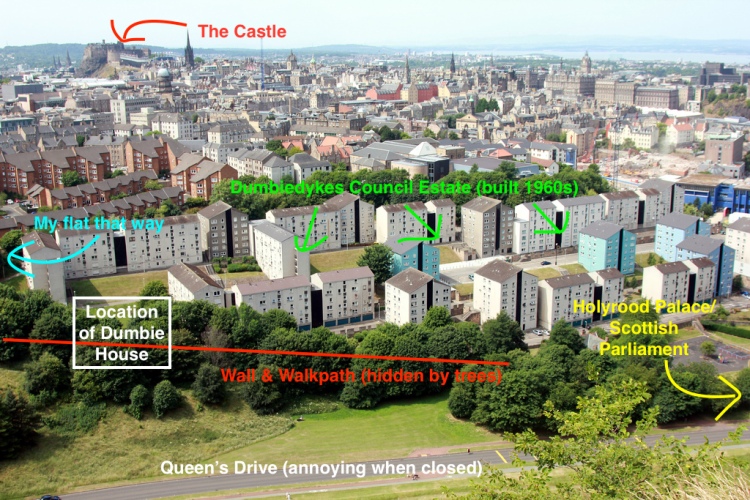

Did you know that of all the UK, Scotland currently hosts the largest urban population of refugees? Yep, Glasgow.

The local authorities that currently host the largest number of asylum seekers (waiting on refugee status) are Glasgow (3,799), Liverpool (1,622), Birmingham (1,575), and Cardiff (1,317). But the largest asylum seeker populations are actually in North West (10,111), the West Midlands (5,431), Yorkshire and the Humber (5,258) and London (5,084).

By September 2016, asylum seekers were ten times more likely to live in Glasgow than anywhere else in the UK. Seems the ‘Weegies were okay with this! (Photo credit)

Although asylum seekers are allocated Home Office accommodations in Glasgow, decisions on their applications are not within the remit of the Scottish authorities. Everything is decided through a centralised, federal system. But while one waits on their application, one can be “dispersed” anywhere within the system without one’s choice taken into account. This means that local authorities and NGOs must compensate for shortages in financial support, issuing documentation and allocated housing.

Fortunately, there’s multiple Scottish/Glaswegian charities willing to help: Scottish Refugee Council, Refugee Survival Trust, Positive Action in Housing, and Scottish Faiths Action for Refugees, among others.

To my great surprise, I googled “Glasgow, refugees, asylum seekers, bad, 2018” to find recent negative news stories about asylum seekers in Scotland. To my shock, I found nothing that denotes a systemic problem between asylum seekers and the local populations. Instead, I googled “Glasgow, refugees, asylum seekers, 2018” and found headlines within the last 6 months like this:

- Lifelong Rangers fan from Sudan shares his incredible story

- Syrian refugees are enjoying life in Renfrewshire with help from Paisley resettlement team

- Glasgow council in bid to house asylum seekers

- Damascene street food – everything you need to know about Scotland’s delicious new trend

Of course, there must be bad news stories… and they appear to be coming from Scottish charities. One independent news source, called The Ferret, reported that charities had doled out record amounts of emergency grants to asylum seekers in 2017 – over £110,000 to be precise. And, at £80 per grant, that’s a huge number of asylum seekers deemed to be in crisis in Scotland.

Why is it so high, the Ferret asks? Due to delays on documentation, poor housing, no access to work or benefits while waiting on one’s application, etc. Basically everything I’ve already written. In fact, The Ferret calls it the “invisible epidemic” of refugee destitution. Evidently, Scottish charities are facing the same challenges as their brothers and sisters south of the border.

Did you know that Scotland allows asylum seekers and refugees full access to the NHS?

All refugees in the UK have immediate free access to healthcare provided by the NHS. Asylum seekers are also entitled to free “urgent care” (also called “primary care”) while in the UK. But “secondary care,” such as getting a specialist to check that never-ending ear infection, or receiving mental health support, or chemotherapy if you have cancer, all those types of long-term “secondary care” benefits are not provided to everyone.

In England, those refused asylum are required to payfor secondary health services. However, in Scotland, refugees and even refused asylum seekers (those deemed as having no recourse to public funds “NRPF”) have full access and treatment on the same basis as any other UK national. Also, all prescriptions are free! Sensational.

So what?

The broader immigration system in the UK is flawed, to put it mildly. Asylum seekers like Nesrîn, an Iraqi Kurd, and her two children, survive on just £37.75/week. She comments that:

They give us asylum benefit so we will not beg, but actually we are begging. Sometimes I cry for myself; everything is secondhand, everything is help. I can never do something for myself… When you become a mum you have everything dreamed for your daughter, and I can’t do anything. I’ve given up, actually.

I can’t imagine just how powerless an asylum seeker must feel in this country. After fleeing violence, war and persecution in their homeland, they arrive on British shores to only find a hostile and monstrous bureaucracy awaiting them.

But, fortunately, Scotland’s treatment of refugees is a cut above the rest. By giving asylum seekers the right to vote, you are giving them a voice. By giving asylum seekers access to full healthcare, you are giving them a chance to live. By creating national strategies for local governments, communities and charities, you are giving refugees a chance to learn English, get a job, find a home, receive an education and integrate into Scottish society. These are remarkable steps in a direction that is supportive, inclusive and diverse. As Sabir Zaza, Chief Executive of the Scottish Refugee Council, said eloquently in May 2018:

“ Refugees often flee their homes because their human rights are denied. For people from the refugee community to then have access to all their rights including the right to vote in Scotland is a hugely significant point in their journey towards integration, citizenship and the ability to play an active role in society.”