I made a rather startling discovery. Those who suffer from dementia can still vote in the UK and Canada. “Really?” you may ask. “Really,” I reply.

Voting in an inalienable right in democratic nations. Once you gain the right to vote, it is extremely difficult to lose.

Criminals are some of the only disenfranchised groups. In Britain, a criminal’s right to vote is suspended while you serve your sentence. This is the same for Australia, except prisoners who serve less than three years can still vote. In Canada, criminals still retain the right to vote, regardless of the prison sentence. The United States has some of the most punitive measures against voting for criminals and because it varies drastically between states, I excluded the USA from this article. (Apologies to my American friends, but you can read more about the almost 6 million felons, or nearly 2.5% of voting Americans, who could not vote in the 2012 federal election here).

Voting is a pillar of equality among citizens and the act of voting is a benchmark in a person’s life.

What about the Youth Vote?

Historically speaking, the argument that youth aged 16 and above should get the right to vote is a very recent phenomenon. Before the Second World War, only people aged 21 years and older were given the right to vote in most major western democracies. In the 1970s, this age was lowered to 18 years of age in the UK, Canada, Germany, and France due to the fact that 18 years was the age of military conscription. However, some nations retain 20 or 21 years as the age of suffrage. Only since the 1990s have some nations successfully lowered the youth vote to include 16 year olds. Scotland is one of them.

Over 75% of Scottish youths voted in the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum

After years of campaigning, the Scottish National Party were able to give youth the right to vote in the June 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum. Impressively, over 75% of those youths aged 16 and over (who registered) turned out, compared with 54% of 18- to 24-year-olds. This turnout was considered hugely successful and resulted in Westminster granting new electoral powers to the Scottish Parliament in December 2014. Now, all youths aged 16 and over can vote in both parliamentary and municipal elections in Scotland.

Nicola Sturgeon and the SNP Party campaigned successfully for years to secure the youth vote (Photo from BBC Article)

For the rest of Britain, youth cannot vote in UK general elections until age 18. Although calculating the youth turn-out rates must not be accepted entirely at face value, in the recent general election one statistic claimed that 72% of all 18 to 24 year olds turned out to vote. This means that turn-out rates for young British voters were remarkably high.

Molly Scott Cato said that denying the youth the right to vote because they aren’t responsible enough was “elitist rubbish” (Photo from BBC Article)

British politicians hotly debate the voting age. The Tories believe it should remain at 18, while Labour proposes lowering it to 16. The Liberal Democratics are somewhere in the middle, suggesting it should be only lowered for local elections. The Scottish National Party, who are very popular with Scottish youth, believe it should be lowered to 16 for general elections. My favourite, perhaps, was when the Green Party’s Mary Scott Cato said that arguments that claim 16 year olds aren’t responsible enough to vote is “elitist rubbish.”

Age is Arbitrary: “Childhood” is a Young Concept

Age as a marker is quite arbitrary, especially when you look at it historically. In the wake of the Second World War, when over 15 million children were left homeless and resettlement was a huge crisis, the United Nations defined anyone under the age of 17 as a child. Today, childhood ends in the majority of sovereign states at age 18.

These Polish war orphans at a Catholic Orphanage in Lublin, on September 11, 1946, are among the 15 million children displaced by the war. To expedite the settlement process, the UN defined all children under age 17 as a “child”

But childhood as a historical concept has only been closely examined in the last few decades. That is not to say that children or childhood were never discussed in historical sources. But, similar to race and gender, age was often overlooked, understudied or poorly represented within historical accounts.

In the 1970s, a revival of the historiography of childhood occurred as the result of the book “L’Enfant et la vie familiale soul l’Ancien Regime” (or “Centuries of Childhood,” 1962) by a French medievalist named Philippe Ariès. He argued that childhood was actually a recently-invented modern term, which evolved from the medieval period. Importantly, the concept of childhood was not static but underpinned heavily by the culture of the time. This revolutionized social history and led many scholars to investigate how Europeans transitioned from a pre-children-conscious world to one which had ‘invented’ childhood. (For an excellent overview, see Nicholas Stargardt, “German Childhoods: The Making of a Historiography,” German History, 16 (1998): 1-15).

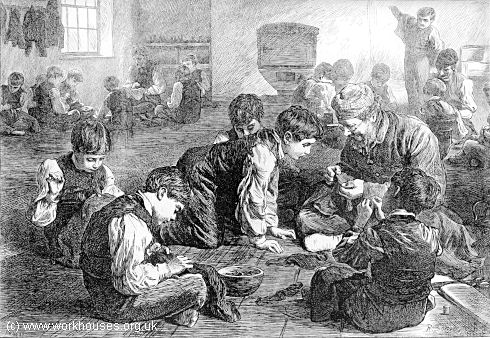

With state intervention in education in the 19th century, and the subsequent child labour laws from the Industrial Revolution, children’s ages became both legally and economically relevant. How old must a child be to work? Can a child be charged with crime? Records of child delinquency are often the first historical accounts that children existed in certain cultural contexts. For example, historians are aware of the punishments of child delinquents in 19th C Irish workhouses, but we know little else about Irish children’s experiences in workhouses who were not delinquent.

Illustration of children in a 19th C workhouse courtesy of workhouses.org.uk

Even biological markers of age are debatable. In the USA, lawyers have used science to argue that grey matter is still being developed well into our 20s in the same area of our brains that regulate self control; this has led to numerous cases where juveniles charged with murder have had their prison sentences reduced. The use of puberty as a reproductive “line in the sand” has also changed in the last few hundred years: the age of puberty today (10-12 years for girls, 12 for boys) is lower today than it was centuries ago (15-16 for girls). And unlike a few centuries ago, “Puberty today marks the transition from childhood to adolescence more than it does childhood to adulthood.” Meanwhile, in the animal kingdom, biologists define animals as adults upon sexual maturity. It seems that neither the historian or biologist can agree about childhood.

And, to make it even more complicated, children as individuals also vary greatly. Children’s experiences and what they’re subjected to also vary greatly. When in doubt, think of Joan of Arc, Malala Yousafzai, or Anne Frank.

Anne Frank was just 15 years old when she died in Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp

So what does this have to do with voting?

If our definitions and beliefs about childhood are culturally dependent, then the ages we assign it, or the assumptions we have about it, are a product of our culture, and not necessarily an authentic reflection of “childhood.” (If such a thing actually exists).

During the medieval era, children were considered “little adults” who needed to be civilized, which presumes that children are born with inborn rationality and intelligence, but lacking social graces. A medieval parent therefore viewed childhood as a rigorous lesson in civility.

During the Medieval era, children were viewed as “little adults” and as as Bucks-Retinue points out, even their clothing was just “smaller versions of adult clothes.”

But today’s parent does not view it quite like that. Due to the legality of certain social freedoms – driving a car or drinking alcohol – the state has defined a child in contradictory ways. You can join the military at age 16 in the UK, but you’re not legally entitled to toast the Queen’s health until age 18. The predictable argument is that if you can join the military, drive a car, leave school for full-time work, pay taxes, marry (and thus have the state’s endorsement to be a parent), then you should have the right to vote. I see no fault in this argument.

So why did I start this conversation by talking about people with dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term for various progressive neurological disorders that includes memory loss, anxiety/depression, personality and mood changes, and problems communicating. We most often associate dementia with Alzheimer’s disease, which has no cure. 46 million people suffer from dementia world wide, which is expected to double every 20 years.

In Britain, 1 in 6 people over the age of 80 have dementia, or a total of 850,000. But having dementia, similar to having learning difficulties or other mental health problems, does not preclude you from voting. According to the Electoral Commission’s Guidance:

“A lack of mental capacity is not a legal incapacity to vote: persons who meet the other registration qualifications are eligible for registration regardless of their mental capacity.”

If someone suffers from mental incapacity or physical disability, they may assign a close relative as a proxy to vote for them (These situations are generally meant to help those serving overseas, or temporarily inaccessible, so they can still exercise their democratic rights and, sometimes, must be approved by a health practitioner or social worker). If a proxy is authorised, the Electoral Commission makes is absolutely clear that no one – whether relative, doctor, nurse or lawyer – can decide how to cast that ballot. The choice alone lay with the voter. Period.

In Britain, you cannot vote if you reside in a mental institution due to criminal activity or if you are severely mentally incapacitated and cannot understand the voting procedure. Those with dementia are still legally entitled to vote because it is not considered legally incapacitating (especially in its early stages) and worthy of disenfranchisement. Usually it is not until a doctor is requested to authorise a proxy vote whereupon someone possibly becomes disenfranchised, depending on the doctor’s judgement.

In Canada, 1.5% of the Canadian population (around 480,000) have dementia, most of which experience this after the age of 75. The Canadian Human Rights Act makes it illegal to discriminate against persons based on age or (dis)ability.

Age is the number one risk factor for dementia.

Canada was one of four countries (Italy, Ireland and Sweden) which did not impose any mental capacity requirement (dementia included) upon the right to vote. After a legal challenge in 1992, the call for a minimum mental health requirement was repealed and by 2008, only Nunavut will disqualify someone from voting based upon mental incapacity. Thus, similar to Britain, Canadians with dementia also retain the right to vote.

What does this tell us about our society?

It is impressive that people suffering from dementia (often elderly) still retain this right. This demonstrates that nations like Britain and Canada strongly respect equality among citizens, irrespective of (dis)ability, mental (in)capacity, or age. And, importantly, this demonstrates that these nations honour the incontrovertible democratic rights of its aging and sick citizens. Discrimination is fundamentally not tolerated.

BUT to deny the youth vote while granting it to someone with a progressive neurological condition seems unfair. Should a 16-year-old “child” be considered less politically capable than someone with dementia? Is that fair?

Youth Vote vs. “Elderly” Vote

In my frustration at this quandary, I read a provocative and humourous commentary calling for disenfranchising all elderly in Time Magazine. Joel Stein said simply “Old people aren’t good at voting”. Although Stein avoided getting his hands dirty with dementia, he highlighted the “out of touch” policies endorsed by “old people”: They’re twice as likely to be against gay marriage, twice as likely to be pro-Brexit and nearly 50% more likely to say immigrants have a negative impact on society. Although funny, I am a staunch supporter of democracy and believe we should enfranchise people even if we disagree with them. That’s the point of democracy: to find consensus among disparate voices. Young, old, sick, healthy, rich, poor, all should be allowed to vote.

In June 2017, Justin Trudeau and Barack Obama had an intimate dinner

Justin Trudeau and Barack Obama recently enjoyed their enviable bromance over a candlelit dinner in a little Montreal seafood restaurant. They spoke of a great many things, but one was “How do we get young leaders to take action in their communities?”

Such conversations among politicians reflect a growing interest to include the youth’s voice and agency within our political process and communities. If what medievalist Philippe Ariès said is true – that our concept of childhood is culturally-dependent – then how our culture interprets our youth needs to change. Historically speaking, it appears that that change is already beginning. And although Scotland has taken remarkable strides towards giving political agency to Scottish youths, this can be taken even further.

By engaging youths in political process, supporting their agency and action in multiple national bodies and networks, and listening to their needs and incorporating their voices into politics, then our cultural assumptions will shift. In the same way as we honour our elders and our sick, let us honour our youths.