The Battle of Vimy Ridge was one of the costliest and most successful military engagements in Canadian history. Due to the extraordinary bravery of thousands of Canadians, the Battle of Vimy Ridge was hard-won against great odds. Today Vimy Ridge is commemorated in Canada as the defining moment when we shed the cloak of the British Empire and defined our own identity on the world stage as a victorious nation.

But.

History really is not the same as remembrance, as I discovered last June when I visited the battlefield. The Vimy Ridge memorial, built in 1936 on land donated by France to “all Canadian people,” has become enshrined in a national narrative honouring Canada’s “coming of age” and “birth” as a nation. With every new busload of Canadian tourists, British schoolchildren, curious Germans, this memorial perpetuates this narrative, while reminding us both the astounding scale of the First World War, and Canada’s role in that international conflict.

Once the feelings of overwhelming awe towards the immense bravery of all soldiers fighting in the First World War passes, and once you dig deeper into Canada’s exact reasons in 1917 for attacking this dreadful graveyard in France, and once you actually question what the hell so many young men were doing in such a devastating conflict, you begin to realise that the way we remember battles has become more important than the reality of what actually happened.

The “Facts” that Fuel Canada’s National Narrative

Vimy Ridge was a heavily fortified seven-kilometre ridge in northern France that held a commanding view over the Allied lines. Previous attempts by the French to secure the ridge resulted in over 100,000 causalities, who lay in the open graveyard between the lines.

Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917. Canadian troops seen here advancing over no man’s land and through the German barbed wire whilst under fire. (Photo: Huffington Post).

The Canadian Corps spent weeks practising the attack. After the disaster at the Somme, British tactics were forced to change. Instead of relying on officers for leadership and strategy (many of whom had been slaughtered at the Somme), regular soldiers were now equipped with enough tactical details to adequately survive if their leader was killed in action. For the first time, regular infantrymen were briefed on the terrain and maps, and encouraged to think for themselves. They were also armed with machine guns, rifle-men and grenade throwers, giving them more versatile tools to overcome obstacles.

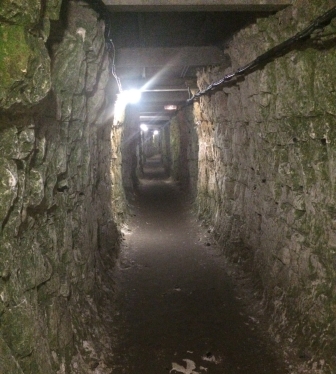

Prior to the Canadian attack on April 9th, 1917, the Canadian Corps had around 1,000 men working on 12 underground passageways. Each of the tunnels housed soldiers, ammunition, water, and communication lines, and most were lit by electricity. See Valour Canada website for more details.

Elaborate tunnels in the rear lines (the longest being 1.2km in length) allowed for quick communication between rear and front line trenches. This also allowed for critical supplies to reach all the troops in the weeks leading to the attack.

But the chief reason for success was the devastating artillery barrage that isolated German trenches and forced German machine gunners to stay in their deep dug outs. A week before the attack, more than a million shells were fired at the German lines, and even targeted at the villages in the rear. The Germans called this “the week of suffering.”

The new artillery fuse (called 106) meant that shells detonated upon impact, rather than burying themselves in the ground, which meant that hard defences could be more easily destroyed. One Canadian observer recorded that the shells poured “over our heads like water from a hose, thousands and thousands a day.”

British General Sir Julian Byng and the commander of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, warned before the attack on Vimy Ridge, “Chaps, you shall go over exactly like a railroad train, on time, or you shall be annihilated.”

On the morning of Monday, 9 April 1917 at 5.30am, four Canadian divisions, attacking together for the first time, overran the German line. Over 15,000 Canadians accompanied by one British division captured the highest part of the ridge (Hill 145) and within three days, the Canadians and British had won the ridge.

But Vimy Ridge was only victorious at a great cost. Nearly 4,000 Canadians were killed and 7,000 were injured.

The Facts Excluded from the Canadian Narrative

The Canadian War Museum website, the Vimy Foundation website, and the Veterans Affairs website of the Canadian government fail to mention German casualties or prisoners, or even recognise Britain’s involvement as anything but ancillary.

Exact figures for German casualties are unknown due to the destruction of records in the Second World War. But we know that 4,000 Germans were taken prisoner, while the Canadian Encyclopaedia estimates that 20,000 Germans were killed or wounded at Vimy Ridge.

One of the reasons for German defeat was the German Commanders’ failure to adequately use a newly introduced defensive tactic called “defence in depth.” Rather than stubbornly defending every foot of captured ground, German armies would allow attacking troops to probe into their territory just far enough to be beyond their supply lines — and then destroy them in a counterattack. The strategy was very effective, but the German defenders of Vimy were given the traditional order to “hold the line” at all costs. The German commander, Ludwig von Falkenhausen, was promptly reassigned after the defeat.

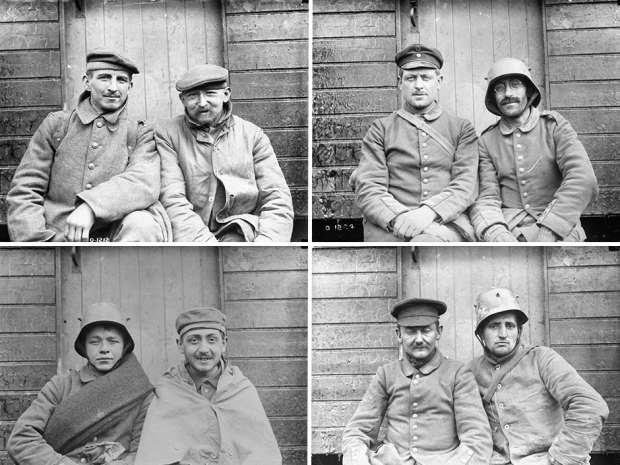

Captured German prisoners after the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 1917. Photo credit: the National Post and Library and Archives Canada.

In the aftermath of Vimy Ridge, German soldiers were photographed smiling after being taken prisoner. This, despite the fact that Canadians had earned a grim reputation for killing those who surrendered. (For an excellent article on this, see Tim Cook’s The Politics of Surrender). But smiling for the camera was no coincidence. A year previously, Germany had suffered through the “turnip winter”, when adults were living on just 1,200 calories a day. So, becoming a POW often meant receiving better rations. Also, the Germans had just undergone weeks of night attacks and raids on their trenches. They were obviously exhausted and relieved to be no longer fighting.

Despite Canadian proclamations of victory, Germans viewed Vimy Ridge as a draw rather than an outright defeat. Historians, such as Andrew Godefroy, admit that due to a lack of sources, it is difficult to fully reconstruct events on the German side. But he revealed that although General von Falkenhausen was assigned most of the blame for losing the ridge, other commanders including General Georg Karl Wichura and Oberstluetnant Wilhelme von Goerne, received medals for their leadership. Also, because the Canadians took the ridge but failed to break the German line, the Germany army recognized, to some degree, that Vimy Ridge had not entirely been a defeat.

Most importantly, the Battle of Vimy Ridge was strategically insignificant to the outcome of the war. Other battles, such as Amiens and Cambrai had far greater impact. As historian Andrew Godefroy writes in Vimy Ridge, a Canadian Reassessment: “To the German army the loss of a few kilometres of vital ground meant little in the grand scheme of things.” After Vimy Ridge, the repute of Canadian troops was certainly increased, especially as elite shock troops in 1918, but Vimy Ridge itself was not strategically important.

Commemorating Vimy Ridge: Let’s Build a Memorial!

After the First World War, nations devastated by conflict erected thousands of monuments (both large and small) to acknowledge those who died. France and Belgium donated sections of land to its allies for the purposes of commemoration. And Vimy Ridge was one of eight battle sites (five in France and three in Belgium) awarded to Canada.

In 1920, the newly established Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission organized a competition for a Canadian memorial to be erected on each site. Walter Allward, an experienced sculptor and a well-known designer of memorials, won the competition in 1921. Due to Vimy Ridge’s vantage point, accessibility and significance, the Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission decided that Allward’s memorial would be built at Vimy Ridge (although it did take 2.5 years to clear the 100 hectare land of unexploded bombs, some of which still remain there today).

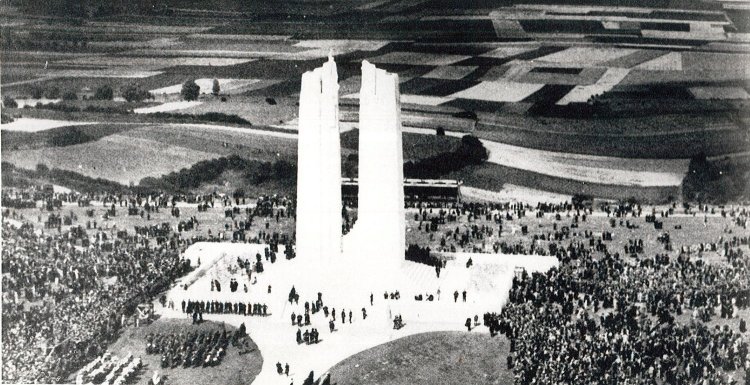

After ten years of construction (it took two years to find a suitable quarry for the limestone, which, ironically, was located in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia where the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife had started the First World War), the memorial was completed in July 1936. 6,000 Canadians were given “Special Vimy” passports by the Canadian government to make the “pilgrimage” to the unveiling.

Over 100,000 spectators attended the unveiling. His Majesty King Edward VIII and various Canadian representatives met with mothers whose sons had died. One veteran remembers: “The service lasted only an hour but never had anyone experienced one more solemn or moving” (Saburo Shinobu, Japanese Branch of the Canadian Legion).

Adorned with twenty sculptures, Allward’s memorial is topped by figures representing the universal virtues of faith, justice, peace, honour, charity, truth, knowledge and hope. The Christian symbolism is obvious and clearly references “traditional images of the Mater Dolorosa (the Virgin Mary in mourning), while the figure spread-eagled on the altar below the two pylons resembles a Crucifixion scene.”

“Between the pylons stands a figure holding a burning torch. Entitled ‘The Spirit of Sacrifice’, it is a reference to one of the most famous poems of the Great War, ‘In Flanders Fields,’ by the Canadian Army Medical Corps officer, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae.” (Canada War Museum)

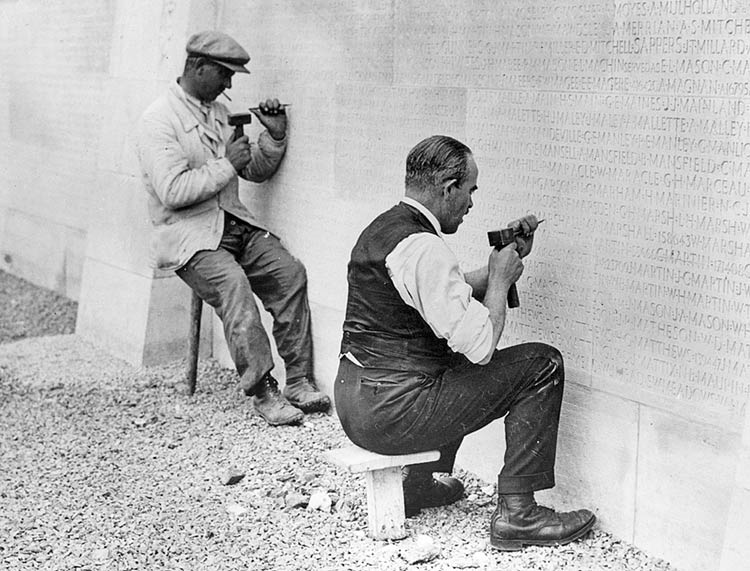

Although not a part of the original design, over 11,000 names of all the Canadians who had died with no known grave are etched into the base of the monument. (Photo from Amerique Francaise)

A maternal figure at the base of the memorial. Note the engraved names around the base.

In 1940, as German armies swept through western Europe, destroying many of the First World War monuments in its wake, Vimy Ridge was exempted. In fact, Hitler visited the monument and was so impressed that he apparently assigned Waffen SS guards to protect it. This prevented regular soldiers of the German army from defacing the monument. As most of the Australian WWI graves and memorials had been destroyed by advancing German troops, this likely saved Vimy Ridge from a similar fate.

Although saving the memorial was also a propaganda stunt to demonstrate Hitler’s goodwill to the conquered French people, perhaps we should all be a little more in awe of a structure that even Hitler himself wouldn’t destroy.

Although the sculpted figures need repair throughout the years, and the monument undergoes regular cleaning, even today the Vimy Ridge memorial looks brand new. Its white stones contrast the blue skies and rolling hills in the large valley below. Just a kilometer away, a new visitor’s centre offers tours to over 700,000 people a year by real Canadian guides. They take groups through the trenches, preserved as they were a hundred years ago.

After the war, the trenches were preserved by pouring concrete into the original sandbags.

Myth Making of a Nation

While I would never minimise the great cost of human life associated to any battle, Vimy Ridge, as a cornerstone of Canadian national identity, is perpetuated by this imposing memorial and its regular commemoration. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, the choice to build this memorial at Vimy Ridge “was a less a result of the battle’s importance than of Vimy’s extraordinary geographic location – a high vantage point with a commanding view, visible from miles around.” And, to be fair to the Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission in 1920, it really is a glorious view.

Canadian historian, Tim Cook, claims that Vimy Ridge was elevated above other Canadian battles, at least partly, for political and national purposes. He addresses the divergence between history and mythmaking in his new book Vimy: the Battle and the Legend (2017):

“Canada is a country – like most – that places little stock in its history, teaching it badly, embracing it little, feeding it only episodically. As Canada developed over time, we cast aside much that grounded us in the past; yet there are some ideas, myths and icons that persistently carry the weight of nationhood. Vimy is one of them.”

The meaning behind Vimy Ridge – whether a bloody sacrifice of countless young men in a war forced upon them by an outmoded commitment to Empire, or perhaps a remarkable story of miraculous nation-forging against all odds – is evolving through a process of forgetting and remembering. With every new busload of Canadian tourists, British schoolchildren, curious Germans, and bewildered Americans, Vimy Ridge is reinterpreted and reconceptualised again and again to the waves of spectators in awe of its remarkable history.

But what I asked myself, one hundred years after the Canadians had won this beautiful vantage point in France, while standing under its majestic pillars on a sunny day in June 2017:

What would we remember of Vimy Ridge if it wasn’t for this impressive memorial?

Vimy Ridge is both a lesson in history and a lesson in remembrance. While Vimy Ridge might unify the two in one immaculate feat of human creation, they are not synonymous. The Battle of Vimy Ridge was an epic victory, where men from each corner of Canada joined together for the first time in a victorious campaign against their sworn enemy. But it wasn’t entirely Canadian – it was led by a British officer and supplied by British provisions. And it wasn’t entirely a victory – it had no decisive impact on the war and the German lines remained intact. Despite those important details, remembering Vimy Ridge at this grand memorial is a testament to a country mourning the great loss of its youngest citizens.

This is truly a lovely review of the actual battle waged at Vimy Ridge but also of the monument. Of course the question always is: when will the world learn to live in peace and to accept others and the diversity of our beautiful planet and it’s people.

LikeLike

Great piece, Chelsea. Love your work and your blog. We visited Vimy and Amiens in September and it was spectacularly moving. What really stood out was that even 100 year laters, the greatest loss of Canadian life in a single day was during the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Thanks for the great read, can’t wait to see what’s next!

LikeLike

Hi Farah! I’m glad you visited it! Very incredible to see in person, I think. Although it’s drilled into our heads in school about Canada “coming of age” I’m not sure the lads on the battlefield viewed it quite like that. But every nation has it’s myths and legacies, and this is definitely Canada’s. Thanks for your comment! xo

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading your excellent review of the Vimy Battle. Certainly learned some new history and new perspectives. I appreciate the thoroughness with which you do your research into the topics on which you write. Keep up the great work!

LikeLike

Thank you, Marilyn! I appreciate any and all comments, as sometimes I feel like I’m writing into a black hole – ha! So I’m glad to hear it’s well-received. Thank you! I’ll keep it up!

LikeLike

Excellent read Chelsea. It’s truly remarkable what these men faced. The photos and descriptions make it all the more real to me. Proud to be Canadian!🇨🇦

LikeLike